Punctuation or Intonation Morphemes in Otomangean LanguagesCheryl A. Black

PDF version available

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (1) | –¿Xi | bichia | cua'ane?– | nilla. | ¡Chenu | aca | eliñi | xadañi | ra! |

| what | day | place-3I | S-say-3R | when | is | fiesta | Rincon | ! | |

| '–What day will it happen?– | he said. | –When the fiesta of Rincon begins!–' | |||||||

| (2) | ¡Neí'ca' | le | rii! |

| that's.right | 2SG | !! | |

| 'O! You're right!' | |||

| (3) | ¿Ni | arqui | lálu | la? |

| S-say | heart | more-2SG | ? | |

| 'Would you like more?' | ||||

| (4) | ¿A | ri'ilu | beya' | xi | uri'i | xeyua? |

| ? | H-do-2SG | know | what | C-do | uncle-1SG | |

| 'Do you know what my uncle made?' | ||||||

| (5) | –¿Xie' | la | aca | nu | lu' | uya | lálu | nu | cha' | lálu | stucu?– | ninchu | lu | niyu. | |

| DOUBT | no | P-be | and | there | C-go | already-2SG | and | P-go | already-2SG | another-one | S-say-3F | face | man | ||

| '–You didn't just go there and now you're going to go again?– she said to the man.' | |||||||||||||||

| (6) | Nzi'a | che | ri'. |

| H-go-1SG | now | EXPECTS.NEG | |

| 'I'm going now, is that all right with you?' | |||

2.2 Alacatlatlazala Mixtec

Data provided by Lynn Anderson, p.c.

| (7) | Án | kisa | va'a | ra | síni | yó'o? |

| ? | C-do | good | 3M | hat | this/here | |

| 'Did he make this hat?' | ||||||

| (8) | Ná | koto | yó | tá | kixaa | ra, | ni'. |

| HORT | P-look | 1INC | if | P-arrive | 3M | DOUBT | |

| 'Let's see if he comes or not (but I doubt it).' | |||||||

| (9) | Nana! | Nana, | ra! |

| mother | mother | URGENT | |

| 'Mother, mother, come NOW!' | |||

| (10) | Kondoo | na | inka | kivi, | che. |

| P-stay | 3PL | other | day | HEARSAY | |

| 'They'll stay another day, they say (or someone says).' | |||||

| (11) | Kóni | ra | no'o | ra | koni, | nikúu. |

| CON-want | 3M | P-go-home | 3M | yesterday | CF | |

| 'He wanted to go home yesterday, but he didn't.' | ||||||

| (12) | Yuku | kúu | takaa, | kánva'a!? |

| who | CON-be | man-that | AMAZE | |

| 'Who in the world is that man?' | ||||

2.3 Copala Trique

Copala Trique has many such punctuation or mood markers, all of which occur in final position. Some are exemplified here, taken from Hollenbach (1995).

| (13) | Ca'anj32 | Migueé4 | a32. |

| C-go | Michael | . | |

| 'Michael went.' | |||

| (14) | Ca'anj32 | Migueé4 | á4. |

| C-go | Michael | !! | |

| 'Yes, Michael did go.' | |||

| (15) | Ca'anj32 | Migueé4 | ei32. |

| C-go | Michael | ! | |

| 'Yes, Michael did go.' | |||

| (16) | Ca'anj32 | Migueé4 | rä'2. |

| C-go | Michael | " " | |

| 'Michael went, they say.' | |||

| (17) | Ne3 | ca'mü2 | Migueé4 | ma'3. |

| no | C-speak | Michael | — | |

| 'Michael did not speak.' | ||||

| (18) | Ca'anj32 | Migueé4 | ná'3. |

| C-go | Michael | ? | |

| 'Did Michael go?' | |||

| (19) | Däj1 | vaa32 | yatzíj5 | gä2. |

| how | exist | clothes | ? | |

| 'How are the clothes?' | ||||

| (20) | Tanuu3 | ro'3, | ca'anj32 | so'3 | Ya3cuëe2 | a32. |

| soldier | , | C-go | 3 | Oaxaca | . | |

| 'As for the soldier, he went to Oaxaca.' | ||||||

3 The Analytical Issues

The analysis of these punctuation morphemes is unclear. The initial assumption would be that they are heads, such as C0. This works well for the case of the initial markers, but not for the final ones, since these languages are strictly VSO with all heads initial. The hypothesis that they are simply adjoined to the clause is problematic because at least some of the markers may occur in embedded clauses which are selected by a higher predicate.

So are these morphemes (other than perhaps the initial yes/no question marker) part of the syntax at all? There is quite a body of literature on the relationship between prosodic structure and syntactic structure: for examples see Selkirk (1978, 1984, 1986), Nespor and Vogel (1986), Hayes (1989), and the articles in Inkelas and Zec (1990). Selkirk (1986) proposes an edge-based theory for mapping S-structure into prosodic structure which allows reference to an edge of an X'-constituent. This is extended by Hale and Selkirk (1987) for Papago to include reference to the government relation, and by Aissen (1992), following their lead, for the Mayan languages. Aissen (1992:57) claims that the algorithm for determining Intonational Phrase boundaries in Tzotzil maps the right edge of an ungoverned Xmax to the right edge of an Intonational Phrase. This algorithm correctly predicts the distribution of the Tzotzil clitics un and e.

A similar algorithm for determining Intonational Phrase boundaries may be correct for the Otomangean languages. But the big difference is that (with the exception of the ro' 3 in Copala Trique which acts like a comma) the punctuation morphemes do not simply attach to the end of any Intonational Phrase, but only to certain types of phrases. For the most part, it is these morphemes themselves which signal the type of phrase involved, much like intonation does in English. Cases like ma' 3 and gä 2 in Copala Trique, which only occur on negative-marked phrases and content questions, respectively, make it clear that it is crucial to know what type of phrase an Intonational Phrase is. Neither the edge-based theory (Selkirk 1986) nor the relation-based theory for mapping syntactic structure to prosodic structure (Selkirk 1984, Nespor and Vogel 1986, Hayes 1989) has any mechanism for obtaining this information. Hyman (1990) suggests that features such as [+wh], [+imp] and [+neg] must be marked on the Intonational Phrase if the syntactic phrase is so marked. This could be achieved by passing head features from the syntactic phrase to the Intonational Phrase.

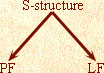

A remaining issue raised by the majority of the markers here (and which also pertains to 'normal' intonation/punctuation in other languages) is what the interface is between the phonology (PF) and the semantics (LF). The basic model of the grammar in the Principles and Parameters framework maps S-structure to PF and LF:

If these 'morphemes' only really exist at PF, then how are they interpreted?

References

Aissen, Judith. 1992. 'Topic and focus in Mayan.' Language 68:43–80.

Hale, Kenneth, and Elisabeth Selkirk. 1987. 'Government and tonal phrasing in Papago.' Phonology Yearbook 4:151–183.

Hayes, Bruce. 1989. 'The Prosodic Hierarchy in meter.' Phonetics and Phonology, Volume 1: Rhythm and Meter. New York: Academic Press.

Hollenbach, Elena E. 1995. Gramática popular del Trique, versión preliminar, Tucson: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano.

Hyman, Larry M. 1990. 'Boundary Tonology and the Prosodic Hierarchy' in Inkelas and Zec: 109–125.

Inkelas, Sharon, and Draga Zec, eds. 1990. The Phonology-Syntax Connection. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nespor, Marina, and Irene Vogel. 1986. Prosodic Phonology. Dordrecht: Foris.

Persons, David D., Cheryl A. Black, and Jan A. Persons. 2000. La Gramática del Zapoteco de Lachixío, versión preliminar, Tucson: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, A.C.

Selkirk, Elisabeth O. 1978. 'On prosodic structure and its relation to syntactic structure' in T. Fretheim, ed. Nordis Prosody II. Trondheim: TAPIR.

Selkirk, Elisabeth O. 1984. Phonology and Syntax: the relation between sound and structure. Chicago: MIT Press.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1986. 'On derived domains in sentence phonology.' Phonology Yearbook 3:371–405.

Endnote

1 Abbreviations used include: Pronouns: 1INC 'first person inclusive'; 1SG 'first person singular'; 2SG 'second person singular; 3 'third person'; 3F 'third person feminine'; 3I 'third person inanimate'; 3M 'third person masculine'; 3PL 'third person plural'; 3R 'third person respectful'; Aspect markers: C 'completive'; CON 'continuative'; H 'habitual'; P 'potential'; S 'stative'; Other: CF 'contrafactual'; HORT 'hortative'. [Back]